From Peterloo to the Euros: why real life matters

By Xanthe Vaughan Williams

W e recently gathered together the whole of Fourth Day’s UK team, minus two unfortunate colleagues who were isolating, for the first time in over 15 months.

A year of lockdowns had already removed any doubt about whether I personally need to be with other people for my brain to function properly, but this gathering brought home how much it matters in the broader context of the media. We all know that some of the best stories come from travellers and that “being there” on the day counts (just look at the price of Wembley tickets) but I wonder whether we also need to consider the cost of not being there.

Our get-together was in Manchester and one of the day’s events was a walking tour of the city in the context of the Manchester Guardian, which is celebrating its bicentary this year. (The paper simply dropped the “Manchester” part of its name when it moved to London in 1964.)

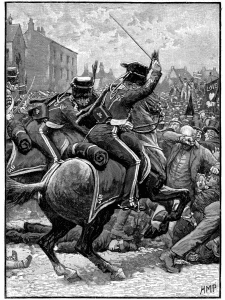

One event discussed on the tour was the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. As our knowledgeable guide, Jonathan Schofield , gave us an account of the yeomanry charge into the campaigning crowd which killed eighteen people in St Peter’s Field, he also pointed out the enormous importance of newspaper reports. There were a number of eyewitness accounts, but possibly the most significant factor in raising public awareness of the event was that a writer for The Times, John Tyas, inadvertently got himself arrested and thrown in prison.

Tyas’ account of the event was published in The Times, which boasted a vast readership of around 7,000, and his employer’s fury at his treatment triggered further articles. As a result, the word spread rapidly, particularly once the Manchester Observer had coined the catchy name Peterloo. The Government panicked and cracked down harder, reformers became more focused and cotton merchant John Edward Taylor founded the Manchester Guardian newspaper. The question is, would the story have reached such notoriety nationally if The Times journalist hadn’t been physically present?

Today, with the combination of budget cuts and Covid, there are fewer than ever journalists out on the beat. Trade journalists rarely have time to travel, and local papers can’t afford to have a reporter turning up regularly to courts or council meetings. We have nobody representing “us” who is physically present.

The same problem applies with international news. I remember being shocked, when living briefly in Chicago in the 1990s, by the lack of international news on TV, radio or print. The rationale given then was that the vast majority of American citizens don’t travel abroad (and 11% have never left their home state) so overseas news feels irrelevant unless it directly involves US soldiers.

I’m hoping it’s my imagination that something similar seems to be happening here. During the England-Denmark match, my South African niece was dividing her attention between the football and news about whether Jacob Zuma would be arrested and that the country would thereby avoid a constitutional crisis. I’m ashamed to say that I hadn’t even been aware of the story. It was there on the BBC website, but a long way down the page. This morning, the first nine “top stories” on my BBC app were about football.

Of course it’s natural to be more interested in stories that we can relate to. But part of that comes from the storyteller being someone we know and trust. From our Own Correspondent on Radio 4 works because we hear people who sound a bit like us telling stories of foreign lands. The facts alone don’t engage us. If Gary Lineker had been reporting from Kwa Zulu it’s likely that the Zuma story would have had a great deal more pickup. I hope that travel for everyone returns soon – and that media outlets don’t fall into the trap of thinking that if people want to hear only about the familiar, that’s what they should be offered. We need to keep our minds open – we should all be getting out more.

Image credit for team picture: Jonathan Schofield, our tour guide

Share this: